You’ve been diagnosed with back pain, arthritis, muscle pain, or foot pain, and now you wonder: what’s next? In times of severe pain, many patients receive prescriptions for opioids such as oxycodone (OxyContin®), hydrocodone (Vicodin®), morphine, codeine, or even turn to so-called “natural” options like CBD products. However, both opioids and chronic use of some CBD products can pose serious risks to your health and family if not used properly.

What are opioids?

- Addiction: Prolonged use of medications like oxycodone or hydrocodone can cause physical and emotional dependence.

- Overdose: High doses, especially of opioids mixed with fentanyl, can stop breathing and be fatal.

- Hidden fentanyl: Many illegal opioids contain fentanyl, a substance 50 times stronger than heroin.

- CBD and chronic use: Although CBD may seem like a “natural” alternative, excessive or unsupervised use can lead to psychological dependence, interactions with other medications, and a false sense of security that delays effective treatments.

- Family effects: Addiction affects the entire family, creating emotional tension, financial problems, and risks for children.

Warning signs

- Extreme mood or behavior changes

- Excessive sleepiness or trouble staying awake

- Loss of interest in daily activities

- Missing pills or duplicate prescriptions

- Unsupervised use of CBD products for chronic pain

- Unexplained financial problems

How to get help

If you or a loved one needs help:

- Call the SAMHSA National Helpline: 1-800-662-4357 (available in Spanish).

- Look for local treatment programs with bilingual services.

- Ask your pharmacy about naloxone (Narcan), a medication that can save lives in case of overdose.

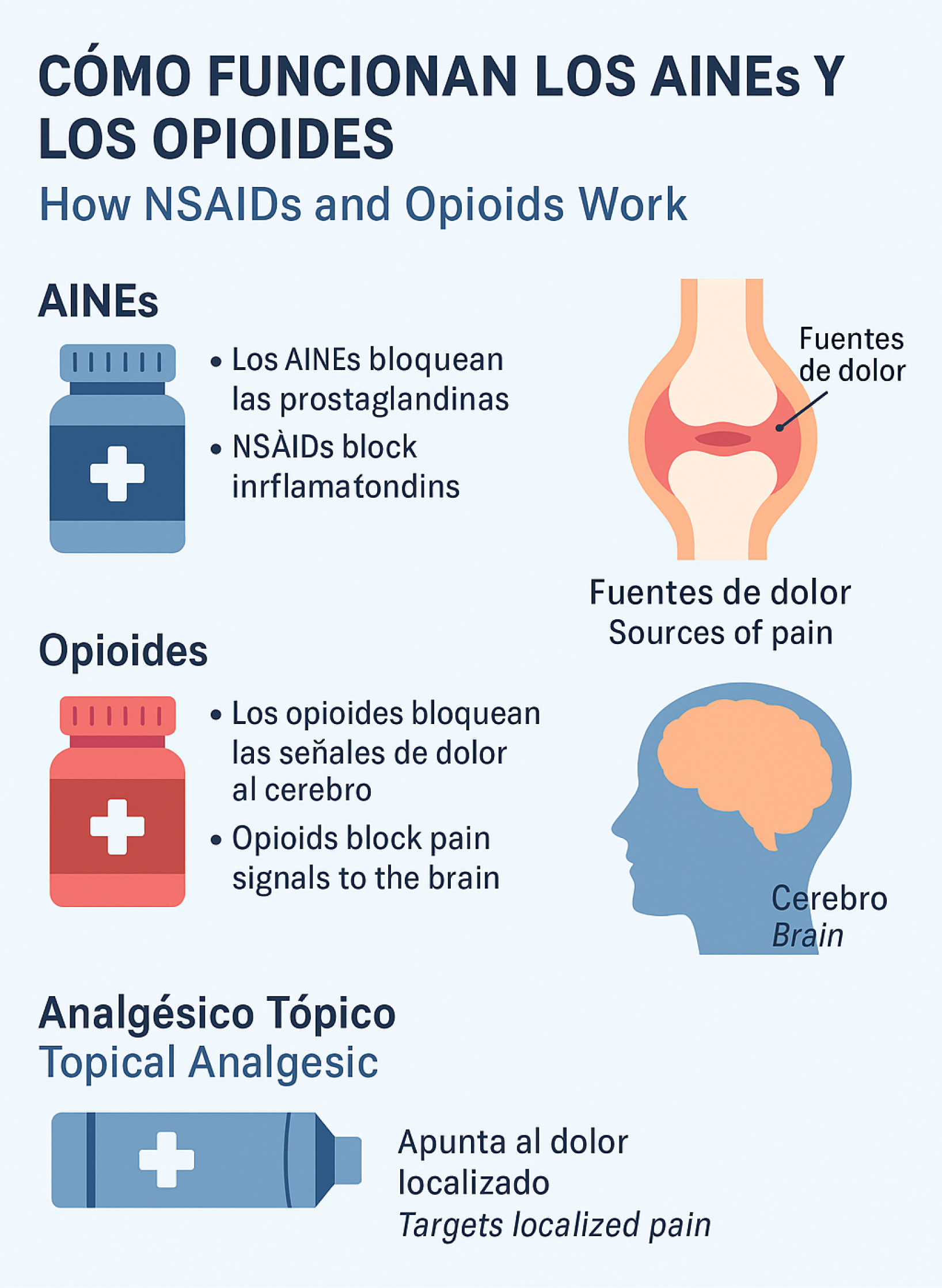

How NSAIDs work and why they don’t cause dependence

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen (FLANAX®), work by blocking substances called prostaglandins, which are responsible for inflammation, pain, and fever. By reducing inflammation directly at the affected site—whether back, joints, feet, or muscles—NSAIDs relieve pain without altering the brain or producing a sense of euphoria.

This means that:

- They do not cause physical or psychological dependence.

- They do not stimulate the brain’s reward centers.

- Their effect disappears when discontinued, without causing withdrawal symptoms.

Pain Relief: Choose Wisely

Why NSAIDs are a safer choice than Opioids

NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, Naproxen)

Mechanism of Action

NSAIDs work by reducing the production of prostaglandins, chemicals that cause inflammation, pain, and fever at the site of injury.

Risk of Addiction

Virtually NO risk of addiction.

NSAIDs do not produce feelings of euphoria and do not activate the brain's reward system.

Common Side Effects

- • Stomach irritation/ulcers

- • Kidney damage (with long-term use)

- • Increased risk of heart attack or stroke

Opioids (Oxycodone, Morphine)

Mechanism of Action

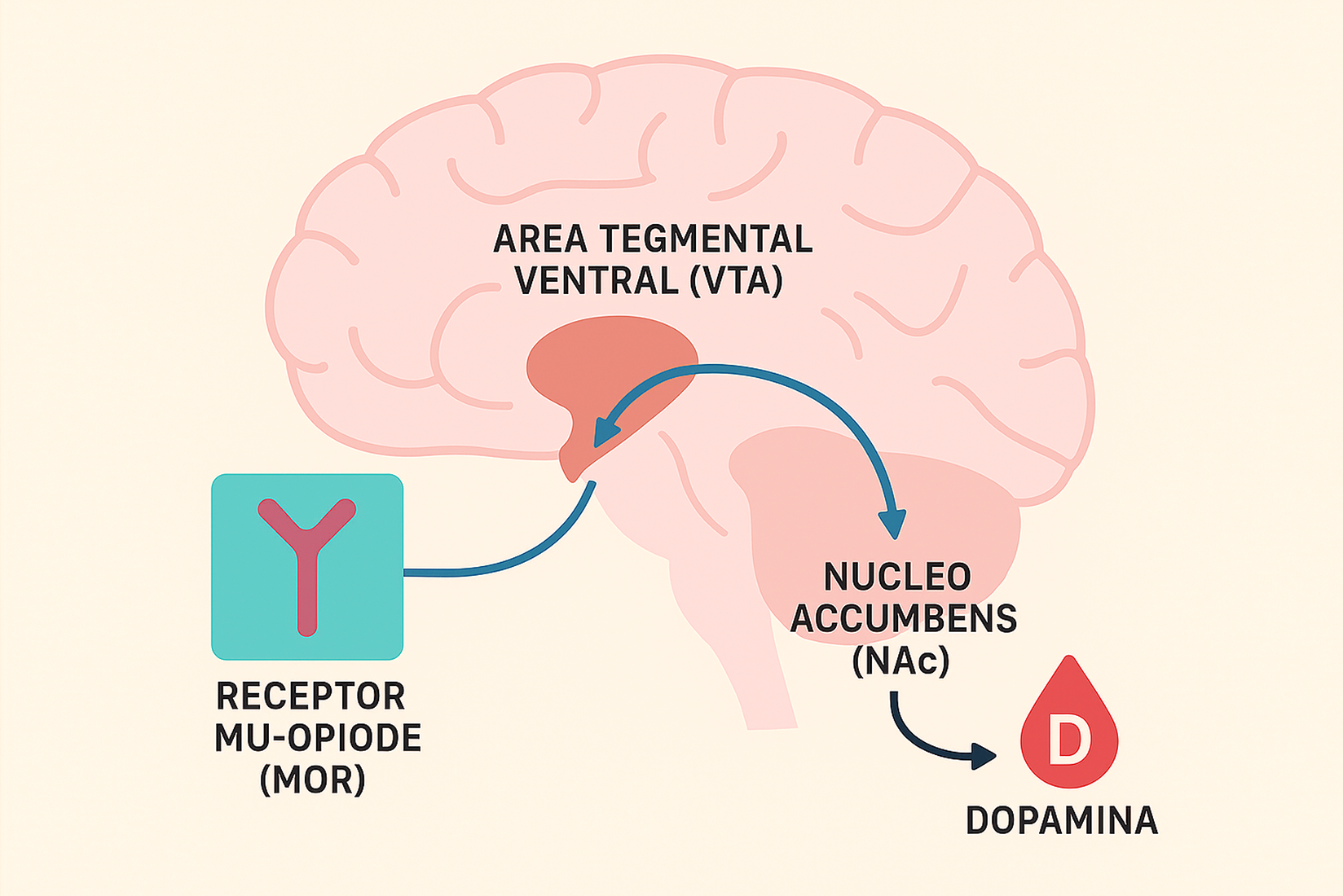

Opioids work by binding to opioid receptors in the brain and central nervous system, blocking pain signals and producing feelings of euphoria.

Risk of Addiction

HIGH risk of addiction.

Their euphoric effects can lead to both physical and psychological dependence.

Common Side Effects

- • Drowsiness, confusion

- • Nausea, constipation

- • Respiratory depression (can be fatal)

- • Withdrawal symptoms

Summary:

When to use NSAIDs:

For mild to moderate pain, inflammation, and fever. Generally available over the counter.

When to use Opioids:

For severe, acute pain (e.g., after surgery or major injury). Use with extreme caution and only under a doctor's supervision.

Always consult with a healthcare professional before taking any medication.

Benefits of topical pain relievers for breakthrough pain

Topical pain relievers, such as lidocaine or capsaicin creams or patches, are an effective tool to control breakthrough pain—that unexpected pain that arises even when on regular NSAID treatment.

Benefits:

- Act directly on the painful area.

- Lower risk of systemic side effects compared to oral medications.